TCM showed 1964's For Those Who Think Young today as part of a festival of teen-surf movies from the '60s. This was United Artists' entry in the genre, though while it has somewhat better production values than the Beach Party movies, it's a lot less fun, and somehow wastes what is, on paper, a pretty good cast; among the people in it are Pamela Tiffin, Ellen Burstyn, Paul Lynde, Bob Denver, and Tina Louise (the latter two both a year away from being stranded on that island together), but in this movie they have so little to do that you long for Frankie Avalon. Most of the material goes to "comedian" Woody Woodbury, while Paul Lynde mostly seems to be Woodbury's stooge -- not the best disposition of resources.

The most memorable part of the movie is the most horrifying; when I saw this on TV over a decade ago, I was completely disgusted and creeped out by this scene. For reasons I have never been able to figure out, Bob Denver is buried in the sand so that only his upside-down mouth is visible, and his disembodied, bearded mouth and painted chin proceed to lead a musical number.

Again, it makes you kind of appreciate the Beach Party franchise, where the numbers were silly, but at least they were fun rather than gross.

By the way, the musical director and composer for this movie was Jerry Fielding. Which means that Straw Dogs is not the most disturbing movie he scored.

Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Saturday, December 27, 2008

Grudge Match: Mammy Yokum vs. Granny Clampett

When there's a fight between the two most fearsome old ladies in the Hills (either the Ozark or Beverly variety), everyone gets out of the way. Who wins the ultimate feud between Pansy "Mammy" Yokum (Li'l Abner) and Granny (The Beverly Hillbillies)?

I anticipate the obvious objection: this is immovable object/irresistible force territory, and could well culminate in the destruction of Dogpatch, Beverly Hills, and its surrounding environs. But that's a small price to pay for a good fictional-character fight.

Mammy is probably stronger than Granny, but I think Granny has more of a mean streak. Mammy believes that "good is better'n evil becuz it's nicer," and has a certain amount of affection for her son and daughter-in-law, while Granny lives in a constant state of rage and fury against everyone, even those closest to her

Thursday, December 25, 2008

Eartha Kitt: "I'm A Liberal Artist"

Since Eartha Kitt died on Christmas day, most of the initial reports are focusing on "Santa Baby." That certainly wasn't the best song she recorded, but with her approach, the song itself was not the most important thing. Every performer creates a persona, but with Kitt, every number was about her persona as the cosmopolitan sex kitten. It helped if the lyrics were specifically about that ("Monotonous"), but she could make anything sound sexy.

It took a lot of originality, ingenuity and courage to create that persona, to get away with projecting a sexuality that defied racial barriers. Even with that layer of campiness that was necessary to take the edge off and make her acceptable, what she did was still very unusual and kind of daring. For years, movies and Broadway and the rest would only show a sexy black woman if they could find some way of implying that she was only sexy to other black people. (Remember Lena Horne's bathtub scene getting cut out of Cabin in the Sky for that very reason.) But when Kitt sang "Monotonous" in the Broadway and film versions of New Faces of 1952, she wasn't just implying that all men, black or white, find her attractive, she was saying it very specifically.

Jack Fath made a new style for me,

I even made Johnnie Ray smile for me,

A camel once walked a mile for me,

Monotonous, monotonous.

Traffic has been known to stop for me,

Prices even rise and drop for me,

Harry S. Truman plays bop for me,

Monotonous, monotone-eous.

In this 1952 article in Time magazine, just after she'd conquered New York, she explained why she and her record company didn't see eye-to-eye on what kind of songs were "her type":

What is her type?

"That's the problem," says Eartha. "Nobody is able to put a definite type on me. All I can do is keep them guessing. I'm a liberal artist."

She was not the greatest singer, or the greatest actress, or the greatest Catwoman (though she was good at all those things), but she was the best Eartha Kitt imaginable; she created a magnetic, irresistible persona through her varied talents. She was a terrific Liberal Artist.

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

WKRP Episode: "Clean Up Radio Everywhere"

Here's an "issue" episode that does work. It was the last episode of the third season, written at the height of entertainment-industry panic about the Moral Majority. Hugh Wilson got the idea for the episode after his show turned up on a list of shows criticized by Jerry Falwell. What makes the episode work is that it puts characterization first: the episode is first and foremost about Mr. Carlson, the conservative, religious guy running a station whose music he doesn't much like or even approve of. He has more in common with the Falwell clone Dr. Bob Halyers (Richard Paul, who looked so much like Falwell that he actually played him in the movie The People Vs. Larry Flynt) than he has with most of the people who work at his station, and he's initially receptive to the argument that his station is playing music that's a bad influence, because that's what he suspected in the first place. So it's an issue episode, but it's also about how Mr. Carlson has developed as a character since the pilot.

Cold Opening and Act 1

Act 2

Cold Opening and Act 1

Act 2

Friday, December 19, 2008

Critter Casts In Cartoons

Has anybody ever traced the history of human characters in short cartoons? I specifically mean the use of humans as supporting characters in cartoons that are about anthropomorphic animal characters.

For many years, if a cartoon was about a talking animal character, then everybody else in the cartoon would be a talking animal as well. Characters were only drawn as humans if there was some specific reason why they wouldn't work any other way. Like Disney's "The Brave Little Tailor": Mickey is a talking animal; every character he meets in the first part of the film is a talking animal; only the giant is a human, because the term implies a giant human being, not a giant animal.

Now look at a cartoon like "No Hunting," which I wrote about a few weeks back (and if you haven't looked at it, buy or borrow the Chronological Donald Duck Vol. 4 and look at it now). In that cartoon, everybody is a human except Donald, his grandfather, and any animals that are actually supposed to be animals: cows, deer and so on. By the '50s, the rule had completely changed for short cartoons: whereas it was once thought that talking animals should live in a world of talking animals, it became the norm to have your talking animal character surrounded by humans.

One thing that led to this was the development of animal characters who were not quite as humanized as Mickey Mouse. Mickey, and Porky Pig, are basically humans who happen to be drawn as animals. They live like humans, they act like humans, they own animals as pets. The cartoon stars who emerged in the '40s were often animals who actually lived like animals: Tom and Jerry acted like a cat and mouse; Bugs Bunny lives in a hole in the ground, eats carrots, and is menaced by hunters. (These characters are, for the most part, naked, whereas Mickey and Porky and Donald wear clothes.) With a character like Bugs, his adversaries have to be human, and when they're not, they have to be animal-like animals, like hunting dogs or Tasmanian Devils. It wouldn't work if Elmer Fudd were drawn as a dog who happens to go hunting with a gun. The whole thing that makes Bugs work as a character is that he is, as he says, "a rabbit in a human woild." Other factors include the rise of the UPA style, making human characters the in thing.

Not that critter casts ever completely went away. I remember seeing "Daffy Dilly" for the first time and being surprised that the butler in that cartoon was drawn as a dog. I guess they felt that since Daffy had a human-type job in that cartoon, other human-type jobs should be occupied by animals; similarly, in "The Stupor Salesman," Daffy is a salesman and Slug McSlug is an animal character. It's fair to say that if those cartoons had been made a few years later, those characters would have been humans. But Tex Avery was still doing humanized animal cartoons like "Magical Maestro" into the '50s. So it didn't go away, it just beame the exception rather than the rule.

Thursday, December 18, 2008

ARTISTS AND MODELS And Its Mysterious Missing Plot Points

You all know I'm something of an Artists and Models junkie, and I've always been a little frustrated by the lack of material on it: no DVD extras, little background information, few contemporary articles (as another Martin & Lewis movie, it didn't get much promotion other than alerting people that Dean and Jerry were back again), not even a trailer -- there was a print of the trailer auctioned off on Ebay last week, but I got outbid. Drafts of the scripts and correspondence are presumably available in the Hal Wallis archives at the AMPAS library, but I haven't had an opportunity to go there yet.

In the meantime, though, I picked up (for $2.99) a copy of an issue of Screen Stories magazine, a movie fan magazine that specialized in publishing the stories of recent movies in short-story form. (This format would be replaced by the full-length novelization.) The writers for Screen Stories would work on their adaptations based on a copy of the screenplay, but they were not always told about changes that had been made to the script after they got their copy, or scenes that were filmed but cut prior to release. That means that sometimes a "Screen Stories" version will contain dialogue or plot points that were cut from the movie. The Artists and Models adaptation was in this issue I picked up, and in lieu of a script, I thought I'd look at it to see if there were any story points that would clarify some of the perplexing plot gaps in the movie.< As I mentioned in a previous post, the plot sort of falls apart in the third act because the spies inexplicably switch from pursuing Dean Martin to pursuing Jerry Lewis -- without ever actually finding out that Lewis is the one who actually created Vincent the Vulture -- and also because Lewis never finds out that Martin has been turning his dreams into a comic book. (Brief plot recap: Lewis has dreams about a lurid superhero adventure; because he talks in his sleep, Martin writes the dreams down and secretly turns them into the kind of ultra-violent comic book that warped Lewis's mind; a detail from Lewis's dreams turns out to be identical to a secret government formula, and both the Russians and the Feds want to know more about the source of this comic book.)

If the Screen Stories piece is based on the script, then there was supposed to be a scene that would have cleared up both of these points. It's in the scene before the Artists and Models ball, where Rick (Martin) is helping Eugene (Lewis) get ready, while an evil Russian spy (the improbably cast Jack Elam, who apparently loved this change-of-pace part) listens in. In the film, the scene just has Rick and Eugene doing the old comedy fancy-dress routine ("I can't keep this dicky down, Ricky!") followed by Rick telling Eugene that he'll meet the "Bat Lady" at the ball, followed by a cut to Elam listening in. But the scene was apparently supposed to be longer: while looking for an article of clothing, Eugene discovers a copy of the "Vincent the Vulture" comic with Rick's name on it, leading to the following dialogue:

EUGENE: You've been working for Murdock! How could you write a thing like this?

RICK: But I didn't write the book. I just drew it.

EUGENE: Then who wrote it? I want to know who's got the dirty, filthy, nasty mind to dream that story up.

RICK: All right, you have. You dreamed it up. That story is out of your little subconscious. That's what you talk when you talk in your sleep. But don't worry, I didn't cheat you. Half the loot's in the bank in your name.

EUGENE: You mean I dreamed this dirty, nasty, filthy story?

RICK: You got talent, Eugie. You're Steubendale's Edgar Allen Poe.

Then the Jack Elam character was supposed to overhear this, which explains how the Russian spies know that Eugene, not Rick, is the creator of Vincent the Vulture.

I don't know if this scene was cut from the movie due to length (at 108 minutes it's unusually long for a M&L comedy) or if they just ran out of time to film it; because this movie went over budget, several scenes were planned but not made. It seems strange that one of the parts they would choose to do without is the part that's necessary for the whole plot to make sense, but that's Artists and Models for you; it's not a movie where logical resolutions or sensible plot construction are very important. If they had to choose between cutting this scene and cutting the dicky scene, I kind of see why they went for the latter -- in this movie at least.

It wasn't planned that way, and I know that I'm really excusing away some serious flaws of storytelling, but the story problems just don't matter to me the way they would in a less crazy film. In the finished film, the thing that gives it some kind of coherence is not the story but the sense of mounting strangeness; every scene is a little more outlandish than the last, as if the movie starts off making fun of Eugene's "wild comic-book dreams" and ends up becoming one. The Godard comparison is still one that sticks with me; Pierrot Le Fou, which I've called his most Tashlinesque film, starts out with a story that makes some kind of logical sense and winds up as a series of wild stream-of-consciousness cartoon sequences.

Not that there aren't plenty of improvements in the finished film. In this version, when Rick runs out looking for Eugene, who is dressed in a giant mouse costume, and Sonia, dressed as the Bat Lady, he asks "Did a woman in a bat costume and a tall thin rat come out?" In the movie, Eugene is dressed in a heavily-padded mouse costume so that Rick can say one of my favorite lines ever: "Did a bat and a fat rat come out here?"

Also it seems like the original script probably had more references to the idea that comic books are genuinely bad for children -- in one scene as recapped in Screen Stories, Rick sees kids acting violent due to the influence of his Vincent the Vulture comics, and that gives him the impetus to quit drawing the comic. (The scene where he quits is in the movie, but with very little setup.) Tashlin really wasn't kidding about not liking mass-market newsstand comics; at the time the film came out, he gave a short interview where he tried to draw a distinction between good cartooning, which is what he did, and violent trashy comics ("I don't know why kids would read that when Treasure Island is so much more exciting"). But because a lot of the anti-comics lines didn't make it into the final film, the movie as it stands has an almost even balance between anti-comics satire and satire of people who are against comics, making it a more good-natured and interesting look at the cultural moment than it might have become.

If the recap is accurate, there was also supposed to be a scene at the Artists and Models Ball which would explain how Dean Martin gets back together with Dorothy Malone and why she arrives with the federal agents near the end of the picture. This is pretty well expendable, though; neither of those things really need explaining. But it seems a shame to lose any scene with Malone in her ball costume, perhaps my favorite of all the many great, surreal Edith Head costumes in the film. (In a strange way it does seem to convey the idea that if you crossed a prim comic-book artist with a Vegas showgirl, this is what she'd wear.)

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

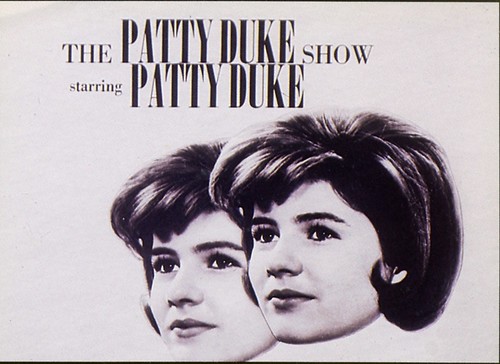

Grudge Match: Patty Duke vs. Hayley Mills

Among the upheavals and conflicts of the '60s, one thing gave hope to the world: the ability of look-alike teenage girls with nothing in common to work together toward a common goal. But now these pairs have decided to work together to commit deadly violence: It's identical long-lost sisters Sharon and Susan (Hayley Mills, The Parent Trap) vs. identical cousins Cathy and Patty (Patty Duke, The Patty Duke Show). Which twins will take the top tier in terrifying toughness?

Sharon and Susan have committed more acts of mayhem than Cathy and Patty, and they have the RAGE (tm) on their side because of the trauma they went through at the hands of their horrible abusive parents (what else would you call parents who split their twin girls apart and never tell them they have a sister?). On the other hand, Cathy and Patty have a wider variety of skills; Cathy has learned a thing or two from living most everywhere, and if Patty eats a hot dog before the fight, she will "lose control" and be an unstoppable killing machine.

Saturday, December 13, 2008

The Best Beatlemania Episode

Paramount's DVD release of Petticoat Junction: The Complete First Season has given me the opportunity to see a bunch of episodes I never saw before (the black-and-white episodes weren't syndicated, and the second half of the first season wasn't released on the Henning estate's previous DVD. This show is rightly regarded as the weakest of the Paul Henning Rural Trilogy, but as usual, the black-and-white episodes are better than the color ones, and this set contains some very good episodes -- mostly the few that Henning wrote himself. (Henning didn't run Petticoat, preferring to concentrate on running The Beverly Hillbillies.

The standout, which I'd never seen before, is "The Ladybugs," written by Henning and his Beverly Hillbillies writing partner Mark Tuttle and directed by none other than Donald O'Connor; inspired by Beatlemania, Uncle Joe organizes the girls (and guest star Sheila James from Dobie Gillis as the fourth member) into an all-girl group with Beatle wigs and ladybug sweaters. As Linda Kaye Henning (Betty Jo) and Pat Woodell (the black-and-white Bobbie Jo) explain in their introduction, this aired on March 24, 1964, little more than a month after the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan for the first time, and as a promotional tie-in, the girls appeared on the actual Ed Sullivan Show as the Ladybugs. The Sullivan footage is not on this DVD, unfortunately; since Paul Brownstein did the special features, I assume he either couldn't find it or couldn't clear it.

It's a funny script, as Henning's scripts usually were, but what surprised me the most was how good-natured it was about the Beatles phenomenon. Not just at the time but for years after, most pop-culture references to the Beatles were fairly derogatory -- remember Allan Sherman's "Pop Hates the Beatles." But this episode is different, even though it was made when the Beatles fad was almost completely new and unexpected. Of course it makes fun of the Beatles and the screaming reactions of their fans (Billie Jo rounds up some cute boys to scream and faint at their act the way girls do in Beatles audiences) and their hair and the rock n' roll business, with Jesse White as a bolo-tied concert promoter who calls himself "Colonel Partridge" -- get it? -- and wants to sign up the Ladybugs even though he hates rock music. But the girls, and young people in general, are not mocked for liking this kind of music, and they get to take a few digs at their parents for not understanding the fad. ("Mom's idea of a hip group," sighs Bobbie Jo, "is Guy Lombardo.") All the satire is genial and gentle with none of the nasty, what's-with-these-crazy-kids tone you usually got in TV episodes about Beatlemania. I just don't think it was in Paul Henning's nature to be nasty about anything; his writing is always so free from malice, and that's one of the things that makes his work hold up so well.

And when it's time for the Ladybugs' big performance in front of their invited audience of screaming boys and Colonel Partridge, Henning actually bothered to clear a real Beatles song for the girls to sing. So while the scene makes fun of this new musical fad, it also assumes that this is a song the audience might enjoy hearing for two and a half minutes.

The song is intact on Paramount's DVD, by the way. And I'm not really sure who's supposed to be who, except that (after an earlier argument about who gets to be Ringo) Betty Jo is their Ringo.

I hope this DVD sells well enough for us to get the second season (the last in black-and-white), when Henning installed his friend and fellow radio veteran Jay Sommers as head writer. Sommers co-wrote nearly all the episodes in the second season of Petticoat Junction, laying the foundation for the style of his own show, Green Acres.

Friday, December 12, 2008

Oh, Porter Hall, You're Always Getting People Into Trouble

Another thing that I like about Miracle On 34th Street, and didn't really think much about until I watched it again recently, is that it's one of the very few 1940s movies to take a dim view of pop psychoanalysis. As anyone who's seen Kings Row or Spellbound scores of other '40s and early '50s movies will agree, this was an era of filmmaking that was drenched in "Dollar-Book Freud" (Orson Welles's term for the Rosebud stuff in Citizen Kane).

But Miracle not only comes out against this kind of thing, it literally makes it the most evil force in the whole movie: the villain is Mr. Sawyer (Porter Hall), who uses fake Freudian jargon to convince a nice young man that his acts of kindness are really rooted in guilt, that he hates his father and that he has some kind of horrible buried secret in his past. All this phony psychiatry, used to make people feel that normal human emotions are rooted in something bad, is the one thing in the whole movie that can rouse Kris to anger and violence. And when telling off Mr. Sawyer, Kris mentions that he has respect for real psychiatrists but not for people who just want to use the language to make people question their own mental health. He, and George Seaton, might as well be telling off the whole '40s film industry.

WKRP Episode: "Dear Liar"

I got a request for this episode, the 18th episode of the fourth and final season. Bailey is assigned to do a story on an underfunded children's hospital and, a la Janet Cooke, makes up a composite kid as the focal point of the story.

I'm not that fond of this episode, for two reasons. One, almost everybody seems out of character. (Even Mama Carlson seems out of character and she's not even in the episode -- but since when is she concerned with children's hospitals?) According to the book America's Favorite Radio Station, Hugh Wilson didn't always do a final rewrite on fourth season episodes the way he'd done for the first three seasons; this feels like one of the episodes that doesn't quite have the show's house style.

Second, it cops out every which way in order to keep Bailey or anyone else at the station from actually, intentionally airing a fake story. (And the issue her story is about is pretty innocuous, too.) There's not much point in doing a Janet Cooke episode when the issue is so watered down. The episode does have some good moments, mostly involving Les, but I think it's one of two episodes from the fourth season that feel like they wandered in from Embassy Television or someplace. (The other is "Pills.") This copy is taken from a tape of an original 1982 broadcast.

Cold Open and Act 1 (music: "Mustang Sally" by Wilson Pickett)

Act 2:

I'm not that fond of this episode, for two reasons. One, almost everybody seems out of character. (Even Mama Carlson seems out of character and she's not even in the episode -- but since when is she concerned with children's hospitals?) According to the book America's Favorite Radio Station, Hugh Wilson didn't always do a final rewrite on fourth season episodes the way he'd done for the first three seasons; this feels like one of the episodes that doesn't quite have the show's house style.

Second, it cops out every which way in order to keep Bailey or anyone else at the station from actually, intentionally airing a fake story. (And the issue her story is about is pretty innocuous, too.) There's not much point in doing a Janet Cooke episode when the issue is so watered down. The episode does have some good moments, mostly involving Les, but I think it's one of two episodes from the fourth season that feel like they wandered in from Embassy Television or someplace. (The other is "Pills.") This copy is taken from a tape of an original 1982 broadcast.

Cold Open and Act 1 (music: "Mustang Sally" by Wilson Pickett)

Act 2:

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

A Note From Frank Doyle's Daughter

One of the posts I'm proudest of is my 2005 post about Archie comics writer Frank Doyle, so I was even prouder to get this email from Doyle's daughter (quoted with permission):

I was showing my 88-year-old mom today how to use google, and when we googled "frank doyle archie" your blog post from 2005 was the first on the page. I'm his daughter, Claire, and just wanted to say that I thoroughly enjoyed the post. You totally "got" my Dad's humor. You definitely pegged his style; I am sure from the first line that the bluebird of happiness story must have been his. He had a wonderful sense of humor and absurdity in real life, too, and that came through in his work. It's nice to know that he was appreciated.

Monday, December 08, 2008

The True JTS Moment?

As you know, I believe that Happy Days incorporates more shark-jump points than any other show. So when I watched the fourth season DVD (coming out tomorrow, and with all the music -- surprisingly -- intact and paid for), I was actively looking for other moments that could be seen as shark bait. And I found one: a scene that I remembered as being a possible JTS moment occurred midway through the fourth season. (The Pinky Tuscadero thing is also a definite JTS possibility, of course, but that's the season opener.)

What's JTS-y about this scene is that it takes all the gimmicks of the Fonzie character and incorporates them into less than two minutes of screen time: he inexplicably shows up to save Richie; turns an evil woman good with one snap of his fingers; performs some kind of impossible feat of strength; makes the jukebox play "Put Your Head On My Shoulder" by hitting it. By having all these clichés go off at once, the writers finally completed the transformation of Fonzie into a cartoon superhero, which is what he would be in the actual Jump the Shark episode. So this is, arguably, the moment when Fonzie became a complete parody of himself, and that's a possible definition of a JTS moment.

Are there any other moments you can think of that struck you like that -- where a show put in so many gimmicks and catchphrases at once that it seemed to have gone too far? I know there are lots of characters who turned into parodies of themselves over the years, but I can't think of many who had one specific moment of transition. The only other one I can think of for now is Xander on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, who instantly went from the best character on the show to a bad pod-person parody of himself when he had the slap-fight with Harmony.

What's JTS-y about this scene is that it takes all the gimmicks of the Fonzie character and incorporates them into less than two minutes of screen time: he inexplicably shows up to save Richie; turns an evil woman good with one snap of his fingers; performs some kind of impossible feat of strength; makes the jukebox play "Put Your Head On My Shoulder" by hitting it. By having all these clichés go off at once, the writers finally completed the transformation of Fonzie into a cartoon superhero, which is what he would be in the actual Jump the Shark episode. So this is, arguably, the moment when Fonzie became a complete parody of himself, and that's a possible definition of a JTS moment.

Are there any other moments you can think of that struck you like that -- where a show put in so many gimmicks and catchphrases at once that it seemed to have gone too far? I know there are lots of characters who turned into parodies of themselves over the years, but I can't think of many who had one specific moment of transition. The only other one I can think of for now is Xander on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, who instantly went from the best character on the show to a bad pod-person parody of himself when he had the slap-fight with Harmony.

Saturday, December 06, 2008

Stereo Staging

I've been revisiting some recordings produced by John Culshaw, and once again I'm reminded that I love, absolutely love, "stereo staging" in recordings of theatre pieces (musicals, plays, operas).

When stereo came in, there was a lot of question about whether voices needed to move across the stereo arc -- did listeners need to hear a voice moving when a character moves, or would that just be distracting? Culshaw was one producer who was certain that, as he wrote, "if the baritone needs to flee from the tenor's wrath, he must obviously move away from him." So he and his other producers prepared for each opera recording by writing out all the movements that the characters would make, and then actually rehearsing the singers in where they were supposed to move, even putting numbers on the floor so they'd know where to stand at a given moment. (The singers had to move while singing, because the early stereo setups meant that you couldn't achieve a convincing movement by just panning the voice; it had to be the real sound of moving from one microphone to the next.) His recording of Georg Solti conducting Wagner's Rheingold, the first huge hit in stereo opera -- it stunned everyone by breaking onto the Billboard pop charts -- was full of this stuff.

As Culshaw explained in his liner notes, he not only staged operas from left to right but from front to back, so the voices would move backwards to indicate that they were at the back of the stage. In the first scene of Rheingold, when Alberich the dwarf is chasing the Rhine Maidens around the river, the voices move while the chase goes on, and when one of the maidens swims away to a higher point, she moves to the extreme right side and also moves back a bit (so her voice will be in a different acoustic for her next line). With the recording of Britten's Peter Grimes, even though Culshaw didn't have time to produce it himself, he and Benjamin Britten prepared for the recording by plotting out every movement and perspective: where the door would be in the pub scene, where Grimes' window would be. You can actually hear Peter Pears' footsteps as he walks from left to right, which is certainly something you don't usually hear in a studio recording.

Anyway, while some companies took up this idea for stereo demonstration purposes, not all of them really embraced it, and a few just flat-out rejected it. (When Herbert Von Karajan went to Deutsche Grammophon after recording operas with Culshaw for several years, he tried to talk his German producers into using Culshaw's techniques, but they talked him out of it, preferring to have the voices remain static.) And as time went on and stereo became commonplace rather than a gimmick, most opera recordings no longer had a lot of movement; they'd use such effects occasionally for entrances and exits, but they would not have a singer's voice actually move across the stage to correspond with some movement that would occur in a stage production. Culshaw's successors at Decca kept the technique going for a little while (the first recording of Britten's Death in Venice has the voices moving around more or less as they did in the first stage production), but mostly gave it up after a while. You'll almost never hear an opera recording with a true stereo staging plan.

I understand why this died out, because it's gimmicky and sometimes counter-productive. (Culshaw would sometimes have a whole aria sung in one speaker because the character was supposed to be sitting or standing at the left side of the stage. But as Culshaw's assistant and later senior Decca opera producer Christopher Raeburn pointed out, when someone sings an aria, you should have them dead center; it's just not effective to have the voice at one extreme or the other.) And there are a lot of late '50s recordings of operas, musicals and spoken-word performances that use stereo not just as a gimmick but a really pointless one: they'll have voices bouncing back and forth between right and left for no clear reason, just to show that they can do it. That's irritating and gets in the way of appreciating the performance.

But the basic principle behind the "stereo staging" approach -- that if you're recording a theatrical work, there should be some sense of where people are and why -- is one that I find makes for more exciting listening. Not only because you can follow the singers' movements but because it creates more variety not to have every singer in one position and one acoustic for an entire scene. If a movement is important to the scene, then it makes sense to put it in the stereo spread, the way producers put in important sound effects. (In The Marriage of Figaro, for example, every producer of an audio recording knows he's supposed to put in the sound of Susanna slapping Figaro. Yet they'll leave Susanna in one place for the whole scene, even though she's supposed to come in from offstage, approach Figaro, and then approach other characters.) It's not a big deal, obviously, but it does enhance the experience if done right; it helps make an audio opera recording into a "theatre of the mind" experience.

I think the last recording to really use this technique elaborately, and certainly one of the best, was the 1976 recording of Porgy and Bess by the Houston Grand Opera company (the best of the three recordings of Gershwin's complete score). The producer, Thomas Z. Shepard, who was RCA's head of classical and Broadway recordings, not only filled the recording with sound effects, but incorporated all kinds of audio movements to stand in for movements he'd seen on stage. It's one of the things that makes that recording feel much more theatrical and alive than other recordings of this piece. (Shepard also sometimes used this in his Broadway recordings -- in Sondheim's Pacific Overtures, you can hear the two characters in "Poems" walk from speaker to speaker as they walk across the stage.)

When stereo came in, there was a lot of question about whether voices needed to move across the stereo arc -- did listeners need to hear a voice moving when a character moves, or would that just be distracting? Culshaw was one producer who was certain that, as he wrote, "if the baritone needs to flee from the tenor's wrath, he must obviously move away from him." So he and his other producers prepared for each opera recording by writing out all the movements that the characters would make, and then actually rehearsing the singers in where they were supposed to move, even putting numbers on the floor so they'd know where to stand at a given moment. (The singers had to move while singing, because the early stereo setups meant that you couldn't achieve a convincing movement by just panning the voice; it had to be the real sound of moving from one microphone to the next.) His recording of Georg Solti conducting Wagner's Rheingold, the first huge hit in stereo opera -- it stunned everyone by breaking onto the Billboard pop charts -- was full of this stuff.

As Culshaw explained in his liner notes, he not only staged operas from left to right but from front to back, so the voices would move backwards to indicate that they were at the back of the stage. In the first scene of Rheingold, when Alberich the dwarf is chasing the Rhine Maidens around the river, the voices move while the chase goes on, and when one of the maidens swims away to a higher point, she moves to the extreme right side and also moves back a bit (so her voice will be in a different acoustic for her next line). With the recording of Britten's Peter Grimes, even though Culshaw didn't have time to produce it himself, he and Benjamin Britten prepared for the recording by plotting out every movement and perspective: where the door would be in the pub scene, where Grimes' window would be. You can actually hear Peter Pears' footsteps as he walks from left to right, which is certainly something you don't usually hear in a studio recording.

Anyway, while some companies took up this idea for stereo demonstration purposes, not all of them really embraced it, and a few just flat-out rejected it. (When Herbert Von Karajan went to Deutsche Grammophon after recording operas with Culshaw for several years, he tried to talk his German producers into using Culshaw's techniques, but they talked him out of it, preferring to have the voices remain static.) And as time went on and stereo became commonplace rather than a gimmick, most opera recordings no longer had a lot of movement; they'd use such effects occasionally for entrances and exits, but they would not have a singer's voice actually move across the stage to correspond with some movement that would occur in a stage production. Culshaw's successors at Decca kept the technique going for a little while (the first recording of Britten's Death in Venice has the voices moving around more or less as they did in the first stage production), but mostly gave it up after a while. You'll almost never hear an opera recording with a true stereo staging plan.

I understand why this died out, because it's gimmicky and sometimes counter-productive. (Culshaw would sometimes have a whole aria sung in one speaker because the character was supposed to be sitting or standing at the left side of the stage. But as Culshaw's assistant and later senior Decca opera producer Christopher Raeburn pointed out, when someone sings an aria, you should have them dead center; it's just not effective to have the voice at one extreme or the other.) And there are a lot of late '50s recordings of operas, musicals and spoken-word performances that use stereo not just as a gimmick but a really pointless one: they'll have voices bouncing back and forth between right and left for no clear reason, just to show that they can do it. That's irritating and gets in the way of appreciating the performance.

But the basic principle behind the "stereo staging" approach -- that if you're recording a theatrical work, there should be some sense of where people are and why -- is one that I find makes for more exciting listening. Not only because you can follow the singers' movements but because it creates more variety not to have every singer in one position and one acoustic for an entire scene. If a movement is important to the scene, then it makes sense to put it in the stereo spread, the way producers put in important sound effects. (In The Marriage of Figaro, for example, every producer of an audio recording knows he's supposed to put in the sound of Susanna slapping Figaro. Yet they'll leave Susanna in one place for the whole scene, even though she's supposed to come in from offstage, approach Figaro, and then approach other characters.) It's not a big deal, obviously, but it does enhance the experience if done right; it helps make an audio opera recording into a "theatre of the mind" experience.

I think the last recording to really use this technique elaborately, and certainly one of the best, was the 1976 recording of Porgy and Bess by the Houston Grand Opera company (the best of the three recordings of Gershwin's complete score). The producer, Thomas Z. Shepard, who was RCA's head of classical and Broadway recordings, not only filled the recording with sound effects, but incorporated all kinds of audio movements to stand in for movements he'd seen on stage. It's one of the things that makes that recording feel much more theatrical and alive than other recordings of this piece. (Shepard also sometimes used this in his Broadway recordings -- in Sondheim's Pacific Overtures, you can hear the two characters in "Poems" walk from speaker to speaker as they walk across the stage.)

Wednesday, December 03, 2008

An Old-Fashioned Two-Shot

I watched a bit of The Pelican Brief on TCM the other day -- not much of a movie, but a good-looking one thanks to the late Alan Pakula. There was one scene that was shot in a way that I particularly liked, and I wanted to bring it up because you hardly ever see a scene like this any more, not just now but for many years before 1993 (when this film was made).

The scene features two guys in the back seat of a car, talking to each other about The Conspiracy. It's a two-shot, almost head-on, with each character occupying half of the Panavision frame. And instead of cutting to different angles the way I expected, the scene just plays out all the way through with no cuts; the characters turn toward each other, turn away, turn back, and it's all done in one take. Normally, when you have two characters sitting together and talking, the scene will start with that shot (the master) but quickly cut to closer angles for each character.

I like this kind of shot, for one thing, because it doesn't overstate the importance of a scene. For an exposition scene, or a light comedy relief scene, or any other kind of scene that isn't all that big, all the cutting just seems to make everything bigger than it is: look at that person's reaction, now look at that other person's reaction, now look at his face while he's talking. Cutting within a scene like this makes sense if the characters are seated or standing in such a way that you can't see them both clearly at the same time. But if they are both in full view of the camera at the same time, like in the back seat of a car, why not let the scene play out (and let us enjoy their reactions in real time) instead of pretending that this is the back-of-the-car scene from On the Waterfront?

This doesn't make The Pelican Brief a great film, but I just like that Pakula bothered to shoot a scene that way. I wish more big films -- and little films, too, which seem to me to have too much reflexive cutting -- would rediscover the principle, once well-known, that a short scene often fits better if you don't edit it so much.

The scene features two guys in the back seat of a car, talking to each other about The Conspiracy. It's a two-shot, almost head-on, with each character occupying half of the Panavision frame. And instead of cutting to different angles the way I expected, the scene just plays out all the way through with no cuts; the characters turn toward each other, turn away, turn back, and it's all done in one take. Normally, when you have two characters sitting together and talking, the scene will start with that shot (the master) but quickly cut to closer angles for each character.

I like this kind of shot, for one thing, because it doesn't overstate the importance of a scene. For an exposition scene, or a light comedy relief scene, or any other kind of scene that isn't all that big, all the cutting just seems to make everything bigger than it is: look at that person's reaction, now look at that other person's reaction, now look at his face while he's talking. Cutting within a scene like this makes sense if the characters are seated or standing in such a way that you can't see them both clearly at the same time. But if they are both in full view of the camera at the same time, like in the back seat of a car, why not let the scene play out (and let us enjoy their reactions in real time) instead of pretending that this is the back-of-the-car scene from On the Waterfront?

This doesn't make The Pelican Brief a great film, but I just like that Pakula bothered to shoot a scene that way. I wish more big films -- and little films, too, which seem to me to have too much reflexive cutting -- would rediscover the principle, once well-known, that a short scene often fits better if you don't edit it so much.

Monday, December 01, 2008

Gwenn Common Sense Tells You Not To

Please read Ivan's great post on Miracle on 34th Street (the original, John-Payne-not-John-Hughes version). He rightly points out how "there is a thin coating of cynicism surrounding Miracle, and how the characters in the movie are motivated to do the right thing—for the wrong reasons."

That's one of the things that makes Miracle so much more than another sappy true-meaning-of-Christmas movie; while it pushes the message about the need to have faith and be irrational, it's also very clear-eyed about the fact that people act in rational, self-interested ways. Many of the remakes have forced the characters to become infected with the sentimentality of the premise, turning them into a bunch of mushy fools, like the John Hughes version and the Broadway flop Here's Love (a musical from Meredith Willson, creator of The Music Man, who was so totally out of ideas that he put in his old hit "It's Beginning to Look A Lot Like Christmas under a different name). But the original Miracle plays perfectly well as a romantic comedy about a crazy old coot who brings two people together; it's not trying to inflate itself and it's not trying to drop an emotional anvil on us. Even the ending is played as a goofy joke; it sends us out laughing.

And it also benefits from incorporating some of the neo-realist feel that Fox movies had in the late '40s, by going outside the studio and shooting in New York and inside Macy's. If it had been made a few years earlier it would have been shot entirely in the studio, and that would have made it feel more like a sappy fantasy.

George Seaton, though... he had a good career, but every time I look at his filmography I can't help thinking it should have been better. After a decade as a very successful screenwriter for comedy (A Day at the Races) and sentimental drama (The Song of Bernadette), he was allowed to direct his script for a Betty Grable musical, and it became perhaps her best film, Diamond Horseshoe. He formed a partnership with Fox producer William Perlberg, and they made some good comedies, dramas and musicals for Fox (The Shocking Miss Pilgrim, another Grable musical, has a Gershwin score entirely created from Gershwin's trunk material, with new lyrics by Ira Gershwin). But apart from Miracle, his movies fell into the category of pleasant things to watch on TV on a Sunday afternoon, as opposed to classics. And after he left Fox, the movies were still short of classic status but longer and less fun (The Country Girl, Teacher's Pet). In 1970, when most of his contemporaries were forced into semi-retirement, he had a huge hit by writing and directing Airport -- a movie that felt like it could have been made 20 years earlier -- and then got forced into semi-retirement anyway.

It's enough that he created one classic like Miracle; most directors don't even do that. But given his talent as a writer and his obvious skill at directing actors (many actors got Oscars or Oscar nominations for working with him), I wonder why a lot of his movies feel like they're missing something.

That's one of the things that makes Miracle so much more than another sappy true-meaning-of-Christmas movie; while it pushes the message about the need to have faith and be irrational, it's also very clear-eyed about the fact that people act in rational, self-interested ways. Many of the remakes have forced the characters to become infected with the sentimentality of the premise, turning them into a bunch of mushy fools, like the John Hughes version and the Broadway flop Here's Love (a musical from Meredith Willson, creator of The Music Man, who was so totally out of ideas that he put in his old hit "It's Beginning to Look A Lot Like Christmas under a different name). But the original Miracle plays perfectly well as a romantic comedy about a crazy old coot who brings two people together; it's not trying to inflate itself and it's not trying to drop an emotional anvil on us. Even the ending is played as a goofy joke; it sends us out laughing.

And it also benefits from incorporating some of the neo-realist feel that Fox movies had in the late '40s, by going outside the studio and shooting in New York and inside Macy's. If it had been made a few years earlier it would have been shot entirely in the studio, and that would have made it feel more like a sappy fantasy.

George Seaton, though... he had a good career, but every time I look at his filmography I can't help thinking it should have been better. After a decade as a very successful screenwriter for comedy (A Day at the Races) and sentimental drama (The Song of Bernadette), he was allowed to direct his script for a Betty Grable musical, and it became perhaps her best film, Diamond Horseshoe. He formed a partnership with Fox producer William Perlberg, and they made some good comedies, dramas and musicals for Fox (The Shocking Miss Pilgrim, another Grable musical, has a Gershwin score entirely created from Gershwin's trunk material, with new lyrics by Ira Gershwin). But apart from Miracle, his movies fell into the category of pleasant things to watch on TV on a Sunday afternoon, as opposed to classics. And after he left Fox, the movies were still short of classic status but longer and less fun (The Country Girl, Teacher's Pet). In 1970, when most of his contemporaries were forced into semi-retirement, he had a huge hit by writing and directing Airport -- a movie that felt like it could have been made 20 years earlier -- and then got forced into semi-retirement anyway.

It's enough that he created one classic like Miracle; most directors don't even do that. But given his talent as a writer and his obvious skill at directing actors (many actors got Oscars or Oscar nominations for working with him), I wonder why a lot of his movies feel like they're missing something.

Saturday, November 29, 2008

WKRP Episode: "Nothing To Fear But..."

In the 20th episode of season 3 (written by Dan Guntzelman from an outline by Tim Reid), an unsolved robbery at the station sets off the usual reactions: paranoia, fear, gun ownership and bad parties.

The use of music in this episode is really exceptional, some of the best in the series. There are two sequences that are entirely timed to the music: the robbery in the first scene takes place to "Love Man" by Otis Redding, and when Venus and Johnny are alone in the station, the music is "Just the Two of Us" by Bill Withers and Grover Washington Jr. Using "Just the Two of Us" has become something of a cliché, but the song was brand-new at the time, and it really creates a strange, almost eerie feeling when combined with the dim lights and the characters' nervousness.

The first song in the episode is "Rock Me Baby," also by Otis Redding, and the music during the party scene is by Bob James -- I can't remember the title. Also, this is another episode that shows Les's fondness for singing hit songs from the '50s.

Cold Open and Act 1

Act 2

The use of music in this episode is really exceptional, some of the best in the series. There are two sequences that are entirely timed to the music: the robbery in the first scene takes place to "Love Man" by Otis Redding, and when Venus and Johnny are alone in the station, the music is "Just the Two of Us" by Bill Withers and Grover Washington Jr. Using "Just the Two of Us" has become something of a cliché, but the song was brand-new at the time, and it really creates a strange, almost eerie feeling when combined with the dim lights and the characters' nervousness.

The first song in the episode is "Rock Me Baby," also by Otis Redding, and the music during the party scene is by Bob James -- I can't remember the title. Also, this is another episode that shows Les's fondness for singing hit songs from the '50s.

Cold Open and Act 1

Act 2

Thursday, November 27, 2008

The Swinger Was the One Invented Yay, Yay, Yay

Someone has put the complete movie The Swinger up on YouTube. It is one of the strangest movies of the '60s, not Skidoo strange but close, and it's never been available on home video. This youtube posting will tide us over until TCM shows it on January 23.

This was the third and last movie that Ann-Margret made with veteran director George Sidney. The other two were Bye Bye Birdie and Viva Las Vegas, the movies that made her a star. But only two years later, Ann-Margret's career was in trouble; she'd been working too much in too many terrible movies. (The exception was The Cincinnati Kid, but she didn't really get noticed for that movie, even though she was one of the best things in it -- doing far more with her generic character than most of the other actors did with theirs.) The Swinger was really her last shot at proving she could carry a movie, and so it made perfect sense for her to re-team with Sidney, who adored her and was accused of unbalancing both Birdie and Vegas by giving A-M extra screen time.

But movies had changed a lot in only a couple of years -- that's part of why A-M had gone from star to potential has-been so quickly -- and the kind of mildly-naughty sex comedy suggested by the subject (a goody-two-shoes girl tries to prove she can be a "swinger" to impress a smut publisher) was looking very creaky. The credited writer of the script, Lawrence Roman, had had a success a few years ago with Under the Yum Yum Tree, a sex comedy with no sex whatsoever. Sidney appears to have decided to shoot the film not as a glossy sex comedy but a parody of glossy sex comedies and mid-'60s culture. (He also said that as with Viva Las Vegas, he junked the original script and had most of it rewritten days before shooting started.)

Sidney was always brash and vulgar; that's why he's my favorite of the MGM musical directors, because he's the least tasteful and the most fun. But here he's consciously being vulgar, and making fun of vulgarity. The famous scene where A-M rolls around in paint isn't just a typical George Sidney riot of color, choreography and over-the-top fun; it's a slam on what Sidney and other old pros clearly saw as the smutty, anything-goes culture. (I've always found the scene more disgusting than entertaining.) Like Skiddoo, it's a film where an old-guard director looks at the changing trends in movies and pop culture and tells the audience: that's what you want, you crazy kids? Well, I'll give it to you and then some! A movie made by a director who obviously is disenchanted with the public (Sidney made only one more movie after this and then retired from directing) does not stand much of a chance of succeeding, and indeed The Swinger was a flop.

What keeps it out of Skidoo territory is that it's much more good-natured than Skidoo. Sidney was, as I said, naturally vulgar and silly, so a lot of the scenes in the movie are only slightly more over-the-top versions of the way he would normally do them. And because the movie is in large part a parody of middle-of-the-road sex comedies (the kind Sidney and A-M had both made), it avoids being a grumpy reactionary movie like Skidoo; it parodies "hip" movies but it's also equally merciless toward the "unhip" movies of the era. And I've always wondered if Wayne's World borrowed from the ending, or rather endings, of this movie.

And for Ann-Margret fans, the movie is obviously worthwhile even though it doesn't for a moment ask her to stretch herself or compete with anybody (Tony Franciosa specialized in getting eaten alive by sexy '60s stars; he'd do the same thing with Raquel Welch in Fathom). Sidney used the same cinematographer from Birdie and Vegas, Joe Biroc, and together they were to A-M as Jean-Luc Godard and Raoul Coutard were to Anna Karina.

And I mean that; I was thinking of a comparison to Sidney's use of Ann-Margret, and the comparison that kept coming to mind was Karina in Pierrot Le Fou or Vivre Sa Vie -- the director's fascination with her is so obvious in every shot. Just as Godard's Karina movies wind up being mostly about Karina's changing moods and Godard's feelings about her, Birdie, Vegas and The Swinger are all mostly about A-M and George Sidney's fascination with her, and her beauty, and her strange combination of the adult and the infantile. I wonder, come to think of it, what kind of movie A-M and Godard might have made together. (Another Karina comparison: A-M and Karina are both really creatures of the '60s. After the '60s they were still attractive, still good actors, but not the fascinating cult figures they once were.)

I'll embed the first two parts, and here's a link to the complete movie, in 10 parts on YouTube.

Part 1, the title song followed by a surprisingly long period of A-M free footage:

Part 2, in which A-M meets Tony Franciosa, rides a motorcycle, dances in a leotard while reading a book, and educates herself about smut.

This was the third and last movie that Ann-Margret made with veteran director George Sidney. The other two were Bye Bye Birdie and Viva Las Vegas, the movies that made her a star. But only two years later, Ann-Margret's career was in trouble; she'd been working too much in too many terrible movies. (The exception was The Cincinnati Kid, but she didn't really get noticed for that movie, even though she was one of the best things in it -- doing far more with her generic character than most of the other actors did with theirs.) The Swinger was really her last shot at proving she could carry a movie, and so it made perfect sense for her to re-team with Sidney, who adored her and was accused of unbalancing both Birdie and Vegas by giving A-M extra screen time.

But movies had changed a lot in only a couple of years -- that's part of why A-M had gone from star to potential has-been so quickly -- and the kind of mildly-naughty sex comedy suggested by the subject (a goody-two-shoes girl tries to prove she can be a "swinger" to impress a smut publisher) was looking very creaky. The credited writer of the script, Lawrence Roman, had had a success a few years ago with Under the Yum Yum Tree, a sex comedy with no sex whatsoever. Sidney appears to have decided to shoot the film not as a glossy sex comedy but a parody of glossy sex comedies and mid-'60s culture. (He also said that as with Viva Las Vegas, he junked the original script and had most of it rewritten days before shooting started.)

Sidney was always brash and vulgar; that's why he's my favorite of the MGM musical directors, because he's the least tasteful and the most fun. But here he's consciously being vulgar, and making fun of vulgarity. The famous scene where A-M rolls around in paint isn't just a typical George Sidney riot of color, choreography and over-the-top fun; it's a slam on what Sidney and other old pros clearly saw as the smutty, anything-goes culture. (I've always found the scene more disgusting than entertaining.) Like Skiddoo, it's a film where an old-guard director looks at the changing trends in movies and pop culture and tells the audience: that's what you want, you crazy kids? Well, I'll give it to you and then some! A movie made by a director who obviously is disenchanted with the public (Sidney made only one more movie after this and then retired from directing) does not stand much of a chance of succeeding, and indeed The Swinger was a flop.

What keeps it out of Skidoo territory is that it's much more good-natured than Skidoo. Sidney was, as I said, naturally vulgar and silly, so a lot of the scenes in the movie are only slightly more over-the-top versions of the way he would normally do them. And because the movie is in large part a parody of middle-of-the-road sex comedies (the kind Sidney and A-M had both made), it avoids being a grumpy reactionary movie like Skidoo; it parodies "hip" movies but it's also equally merciless toward the "unhip" movies of the era. And I've always wondered if Wayne's World borrowed from the ending, or rather endings, of this movie.

And for Ann-Margret fans, the movie is obviously worthwhile even though it doesn't for a moment ask her to stretch herself or compete with anybody (Tony Franciosa specialized in getting eaten alive by sexy '60s stars; he'd do the same thing with Raquel Welch in Fathom). Sidney used the same cinematographer from Birdie and Vegas, Joe Biroc, and together they were to A-M as Jean-Luc Godard and Raoul Coutard were to Anna Karina.

And I mean that; I was thinking of a comparison to Sidney's use of Ann-Margret, and the comparison that kept coming to mind was Karina in Pierrot Le Fou or Vivre Sa Vie -- the director's fascination with her is so obvious in every shot. Just as Godard's Karina movies wind up being mostly about Karina's changing moods and Godard's feelings about her, Birdie, Vegas and The Swinger are all mostly about A-M and George Sidney's fascination with her, and her beauty, and her strange combination of the adult and the infantile. I wonder, come to think of it, what kind of movie A-M and Godard might have made together. (Another Karina comparison: A-M and Karina are both really creatures of the '60s. After the '60s they were still attractive, still good actors, but not the fascinating cult figures they once were.)

I'll embed the first two parts, and here's a link to the complete movie, in 10 parts on YouTube.

Part 1, the title song followed by a surprisingly long period of A-M free footage:

Part 2, in which A-M meets Tony Franciosa, rides a motorcycle, dances in a leotard while reading a book, and educates herself about smut.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Movie Musicals, Orchestrations, And Ray Heindorf

The three Warner Brothers wartime musicals released in the new Homefront Collection boxed set are all uneven. (Thank Your Lucky Stars is the best of them because even the weaker segments are at least fun, and the Arthur Schwartz/Frank Loesser score is one of the best ever written for a film musical, but it's not available separately.) But one thing that's consistent in all three of them is the excellence of the orchestral arrangements, and that's due to Warner Brothers' Ray Heindorf, by far the best orchestrator/arranger in Hollywood musicals.

But first let me confess my prejudice about Hollywood musicals: I think most of them are over-orchestrated. That's just my own personal prejudice, not a universal belief; many people are disappointed with the original small-band Broadway orchestrations of South Pacific or The Sound of Music after experiencing the Fox movie versions. But I find that most of the movie-studio orchestrators, equipped with bands much larger than any Broadway pit orchestra, tended to soup everything up too much. The worst was MGM's orchestrator, Conrad Salinger, whose arrangements could drain the life out of a song: he let the strings and brass ride over everything, and cultivated an all-purpose glitzy sound that had no relationship to any trend in popular music at any time in history.

But even better musicians, like Alfred Newman and his orchestrators at Fox or Joseph Lilley's team at Paramount, seemed to let the size of the orchestra overwhelm the songs, rarely providing the kind of wit or distinctive sounds that you got from the best Broadway orchestrators. (Compare, for example, Robert Ginzler's superb orchestrations for Bye Bye Birdie, with their memorable flute-heavy sound and their references to all kinds of different trends in late '50s/early '60s pop, to the bigger, blander arrangements in the movie version. The movie had a bigger orchestra to work with, but the orchestra makes hardly any interesting sounds, while the Broadway orchestra has something new and interesting in almost every bar.)

The exception to this rule is Heindorf, who started at Warners soon after sound came in and stayed there for 40 years, eventually succeeding Leo Forbstein as head of the music department. He orchestrated many non-musical films, including several scores by Erich Korngold, but his specialty was the musical; he orchestrated all three of the musicals in this new DVD box. And of all the big studios, it was Warner Brothers whose musicals had the smartest and snappiest orchestrations, as well as the most awareness of what was going on in pop music at a particular time. Some of that was just inherent in the studio's way of working; they had a more pop-friendly orchestra than Fox's basically classical-oriented group, and they also had the best music mixing department in the business (David Selznick wrote a memo to his music people asking them how Warners was so much better than anyone else at recording music and combining it with dialogue), but some of it is Heindorf.

He had a strong jazz influence in his scoring -- he was a friend and sometime collaborator of Art Tatum -- but he also used the orchestra the way Broadway orchestrators did, making his points with specific instrumental details. He'd let the trumpets or woodwinds comment at the end of a phrase, while thinning out the orchestration while the singer was singing (and if it was someone who couldn't really sing, like Bette Davis, doubling the melody in the orchestra). And when he wanted a "big" sound, he'd get it through a really contemporary, hip sound, rather than a wash of strings or some kind of fake swing arrangement like Alfred Newman would usually give us. And under Heindorf, Warners was one of the few studios to re-orchestrate Broadway scores without trashing them; Yip Harburg wrote a complimentary letter to Heindorf after hearing the orchestrations for his last Warners project, Finian's Rainbow.

Heindorf was also responsible for many of the orchestrations/arrangements in the Busby Berkeley musicals, where he did an amazing job with an impossible task. Instead of having dance arrangements specially written, Berkeley would plan most of his numbers to the refrain of the song, repeated over and over -- meaning that the arranger had to figure out how to play the same song without variation for ten minutes, without getting the audience aggravated. It's a tribute to Heindorf that he was able to make all that repetition tolerable through changes in orchestral color (also, of course, a tribute to Harry Warren that he wrote tunes that can be repeated endlessly). But I think his best work may be on Thank Your Lucky Stars, since he had to work in so many different styles and provide appropriate orchestral support for many performers who weren't singers. And besides, ending this post with Thank Your Lucky Stars allows me to post "Ice Cold Katie" again.

But first let me confess my prejudice about Hollywood musicals: I think most of them are over-orchestrated. That's just my own personal prejudice, not a universal belief; many people are disappointed with the original small-band Broadway orchestrations of South Pacific or The Sound of Music after experiencing the Fox movie versions. But I find that most of the movie-studio orchestrators, equipped with bands much larger than any Broadway pit orchestra, tended to soup everything up too much. The worst was MGM's orchestrator, Conrad Salinger, whose arrangements could drain the life out of a song: he let the strings and brass ride over everything, and cultivated an all-purpose glitzy sound that had no relationship to any trend in popular music at any time in history.

But even better musicians, like Alfred Newman and his orchestrators at Fox or Joseph Lilley's team at Paramount, seemed to let the size of the orchestra overwhelm the songs, rarely providing the kind of wit or distinctive sounds that you got from the best Broadway orchestrators. (Compare, for example, Robert Ginzler's superb orchestrations for Bye Bye Birdie, with their memorable flute-heavy sound and their references to all kinds of different trends in late '50s/early '60s pop, to the bigger, blander arrangements in the movie version. The movie had a bigger orchestra to work with, but the orchestra makes hardly any interesting sounds, while the Broadway orchestra has something new and interesting in almost every bar.)

The exception to this rule is Heindorf, who started at Warners soon after sound came in and stayed there for 40 years, eventually succeeding Leo Forbstein as head of the music department. He orchestrated many non-musical films, including several scores by Erich Korngold, but his specialty was the musical; he orchestrated all three of the musicals in this new DVD box. And of all the big studios, it was Warner Brothers whose musicals had the smartest and snappiest orchestrations, as well as the most awareness of what was going on in pop music at a particular time. Some of that was just inherent in the studio's way of working; they had a more pop-friendly orchestra than Fox's basically classical-oriented group, and they also had the best music mixing department in the business (David Selznick wrote a memo to his music people asking them how Warners was so much better than anyone else at recording music and combining it with dialogue), but some of it is Heindorf.

He had a strong jazz influence in his scoring -- he was a friend and sometime collaborator of Art Tatum -- but he also used the orchestra the way Broadway orchestrators did, making his points with specific instrumental details. He'd let the trumpets or woodwinds comment at the end of a phrase, while thinning out the orchestration while the singer was singing (and if it was someone who couldn't really sing, like Bette Davis, doubling the melody in the orchestra). And when he wanted a "big" sound, he'd get it through a really contemporary, hip sound, rather than a wash of strings or some kind of fake swing arrangement like Alfred Newman would usually give us. And under Heindorf, Warners was one of the few studios to re-orchestrate Broadway scores without trashing them; Yip Harburg wrote a complimentary letter to Heindorf after hearing the orchestrations for his last Warners project, Finian's Rainbow.

Heindorf was also responsible for many of the orchestrations/arrangements in the Busby Berkeley musicals, where he did an amazing job with an impossible task. Instead of having dance arrangements specially written, Berkeley would plan most of his numbers to the refrain of the song, repeated over and over -- meaning that the arranger had to figure out how to play the same song without variation for ten minutes, without getting the audience aggravated. It's a tribute to Heindorf that he was able to make all that repetition tolerable through changes in orchestral color (also, of course, a tribute to Harry Warren that he wrote tunes that can be repeated endlessly). But I think his best work may be on Thank Your Lucky Stars, since he had to work in so many different styles and provide appropriate orchestral support for many performers who weren't singers. And besides, ending this post with Thank Your Lucky Stars allows me to post "Ice Cold Katie" again.

Friday, November 21, 2008

WKRP Episode - "A Simple Little Wedding"

Finally, an episode that's upbeat -- this was episode 19 of season 3, and has Mr. Carlson and his wife deciding to renew their marriage vows, only to find that Mama Carlson tries to take over the wedding just the way she did 25 years ago.

This episode introduced Ian Wolfe as Mama Carlson's butler Hirsch. A wisecracking butler is not exactly an original type of character, but Wolfe, an American character actor who'd been around since the '30s, made something special of the character despite having very few lines of dialogue in this episode, and was brought back several times the following season. Wolfe was like Charles Lane, a character actor who just never seemed to stop working and never seemed to look any different; Loni Anderson had this to say about Wolfe in an interview last year:

This version has all the original music, but I don't recognize the songs, although the last song in the bachelor-party scene is by Otis Redding. Also, two bits of continuity: Herb refers to his drinking problem (and promptly falls off the wagon) and one of the strippers Herb hires is the stripper who he tried to hire for the Ask Arlene job in "Ask Jennifer."

Teaser and Act 1

Act 2 and Tag

This episode introduced Ian Wolfe as Mama Carlson's butler Hirsch. A wisecracking butler is not exactly an original type of character, but Wolfe, an American character actor who'd been around since the '30s, made something special of the character despite having very few lines of dialogue in this episode, and was brought back several times the following season. Wolfe was like Charles Lane, a character actor who just never seemed to stop working and never seemed to look any different; Loni Anderson had this to say about Wolfe in an interview last year:

He had been in every old movie that I ever loved, including a Sherlock Holmes movie. He never looked any older, I thought. He looked just as old in our show as he had like 30, 40, 50 years ago. So, with that, I will never forget that we got to work with him.

This version has all the original music, but I don't recognize the songs, although the last song in the bachelor-party scene is by Otis Redding. Also, two bits of continuity: Herb refers to his drinking problem (and promptly falls off the wagon) and one of the strippers Herb hires is the stripper who he tried to hire for the Ask Arlene job in "Ask Jennifer."

Teaser and Act 1

Act 2 and Tag

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Irving Brecher

Irv Brecher, writer of many Golden Age film musicals and radio comedies, has died at the age of 94. Ivan at Thrilling Days of Yesteryear, a huge fan of Brecher's The Life Of Riley radio series, has a great tribute.

His autobiography, in the works for many years, was completed before he died and will be pubished posthumously in January 2009.

Brecher was one of the great Old Hollywood talking heads, a guy who loved to talk in that perfect comedy-writer's accent of his, and kept you spellbound with wonderful, vividly told stories about every star he'd ever worked with. I first saw him on Saturday Night At the Movies talking about his two films with the Marx Brothers. (When, oh, when is TVO going to make their archive of interviews available to the public?) His scripts for the Marx Brothers were not really among the best they worked with -- but his stories about them were always great. Last year, during the writer's strike, the 93-going-on-94 Brecher appeared in a YouTube video for the WGA, still energetic and intelligent and proud of being a writer.

His autobiography, in the works for many years, was completed before he died and will be pubished posthumously in January 2009.

Brecher was one of the great Old Hollywood talking heads, a guy who loved to talk in that perfect comedy-writer's accent of his, and kept you spellbound with wonderful, vividly told stories about every star he'd ever worked with. I first saw him on Saturday Night At the Movies talking about his two films with the Marx Brothers. (When, oh, when is TVO going to make their archive of interviews available to the public?) His scripts for the Marx Brothers were not really among the best they worked with -- but his stories about them were always great. Last year, during the writer's strike, the 93-going-on-94 Brecher appeared in a YouTube video for the WGA, still energetic and intelligent and proud of being a writer.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

You're Either a Goldfinger Guy Or a From Russia With Love Guy

Oh, one other thing, a James Bond-related thought (which I probably should have posted last Friday, but what the heck): one thing I've noticed about my attitude to James Bond movies is that while I acknowledge that most of the best Bond movies are more or less in the From Russia With Love vein -- fewer gadgets, a more serious tone, more emphasis on characterization -- my favorite kind of Bond movie is the Goldfinger type of wild fantasy adventure, even though there are fewer good movies of this type.

While I acknowledge the superiority of From Russia With Love and On Her Majesty's Secret Service and Casino Royale and maybe even For Your Eyes Only to most of the "wacky" Bond movies, I don't return to them all that often as a group. Okay, that's not fair to FRWL; I do return to that one, because it's one of the two best of the Connerys (and like Goldfinger, it's a superb adaptation of the Fleming novel, though there were fewer changes that had to be made because the source material is stronger).

But with OHMSS, all the stuff that's supposed to make it better as a movie just makes it less entertaining to me as a Bond movie: no Ken Adam sets, few gadgets, lots of character moments and wistful speeches and romantic walking montages. I would much rather see You Only Live Twice, which has a terrible script but never stops trying to show us wonderful things, than On Her Majesty's Secret Service, which pretends that this ridiculous story is supposed to be taken seriously (and thereby falls into one of the traps Fleming himself kept falling into) and takes longer than almost any other Bond film even though it has fewer spectacular sequences to justify its length.

It's true that the big, wacky, silly Bonds are more likely to be bad, whether bad in a fun way (Diamonds Are Forever) or just bad in a bad way (A View To a Kill). The semi-serious ones are more likely to work as movies. But that's the thing: the semi-serious Bond movies are comparatively easy to make. They're not that different from non-Bond spy movies. It's the cartoony Bond movies that are the hardest to pull off, because the sets have to be truly eye-popping, the set pieces truly spectacular and the women truly memorable, and the director has to do all this while preserving the feel of a Bond movie rather than a campy Bond imitation. Goldfinger pulled this off, The Spy Who Loved Me pulled it off, and few others really have succeeded at this all the way through, because it's so difficult.

But while I appreciate what they've done with the reboot, I would like to see the Bond team try a similarly well-thought-out approach to a Goldfinger type of adventure. That's the kind of James Bond movie I'm waiting for.

While I acknowledge the superiority of From Russia With Love and On Her Majesty's Secret Service and Casino Royale and maybe even For Your Eyes Only to most of the "wacky" Bond movies, I don't return to them all that often as a group. Okay, that's not fair to FRWL; I do return to that one, because it's one of the two best of the Connerys (and like Goldfinger, it's a superb adaptation of the Fleming novel, though there were fewer changes that had to be made because the source material is stronger).